Okay, so by now you've absorbed all those tasty amino acids, sugars, fats, vitamins, and minerals. They've passed through the enterocytes and into the bloodstream (with the exception of some fats and fat-soluble vitamins, which at this point are still wandering around lost in the lymphatic system.) But, now that the bulk of nutrients are in the bloodstream, they must be rushing to the four corners of the body, to be shared equally by your cells and tissues, right?

You’re so ignorant, you disgust me.

Of course they aren't! You can't just give them free rein to wander around wherever they please! There could be terrorists in those nutrients. And what do we do to keep out terrorists? We give them a security screening.

So please remove all shoes and jackets, and place all metal and electronic devices in the tray, because you're in line for the hepatic portal system.

The hepatic portal system is the first destination for nutrient-rich blood flowing from the gastrointestinal system. This arrangement is unique to the GI. The blood coming back from non-GI organs drains into veins that lead directly back to the heart, which then pumps that blood through the lungs to pick up some oxygen, then back to the heart again, where the cycle repeats. But the blood from the GI drains into special veins that take a major detour from the normal route. Instead of going back to the heart for re-circulation, they all head straight into the liver.

Why do this? One reason is to give the liver first shot at nullifying any toxins, such as alcohol. Yes, alcohol is toxic to our bodies, a thought so depressing that it makes me want to get drunk and forget it. Then again, alcohol's toxic quality is exactly what we like about it. Drunkenness or even a light buzz is the feeling of alcohol depressing your central nervous system.

We deal with alcohol by metabolizing it with enzymes called alcohol dehydrogenases. They’re present in small amounts throughout our bodies, but are highly concentrated in the liver.1 So, by detouring incoming nutrients through the liver, we give it a chance to diminish alcohol and other toxins before they even reach the rest of the body. This helps to protect us from any poisons present in our foods, and lowers our chance of making terrible mistakes. (Steve, please stop calling me.)

|

| Cellular Architecture of the Liver CC Zorn, A.M., Liver development (October 31, 2008), StemBook, ed. The Stem Cell Research Community, StemBook, doi/10.3824/stembook.1.25.1 |

And finally, there's another advantage to running incoming nutrients through the liver: to give the liver first dibs. You see, the liver is a clearinghouse for many of our body's needs. Carbohydrates and fats are built to order in the liver. Most blood proteins are made in the liver. Amino acids (liberated from proteins in our food) are broken down and/or re-purposed in the liver.3 The liver also supplies DNA bases that other cells in the body are too lazy to make for themselves.4 What an organ, right?

A shortage of any of these vital compounds could be disastrous for the body, so we make sure that the body's provider is provided for before any other organ. For example, if the liver didn't have the energy and ingredients to make DNA bases, cell division would shut down in many part of the body. If the liver's production of blood protein slowed down, it could (among a host of other issues) screw up osmotic pressure and cause edema. And if we didn't get the carbohydrates we need? We’d get very sleepy and then drop dead.

So the next time one of your organs complains about the liver getting all the best nutrients? You look that organ in the face (if the organ is your face) and say, "It earns it."

And now for the next step in the GI...

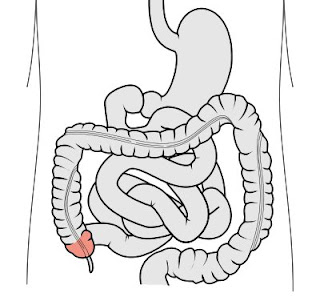

The Cecum

|

| The Cecum, in pink. Image CC Olek Remesz. |

The stomach emptying, all the way at the top of the small intestine, triggers the gastroileal reflex down here at the bottom. That reflex causes contraction of the end of the ileum, which increases peristaltic pressure, forcing the contents through the ileocecal sphincter and into the cecum.

Finally, we've arrived in the first section of the large intestine. Once the cecum starts to fill up, the ileocecal sphincter clamps down tight, preventing any back-flow from the bacteria-rich cecum into the relatively clean ileum.5 Because, gross.

As soon as that shit is through that sphincter, it becomes… you know, shit. In the small intestine, the bacterial content of chyme has been low, because the chyme was constantly shuffled along downhill. Bacteria don’t have a place to gain a foothold in the small intestine, so the only bacteria in chyme are the ones who survived their trip through stomach along with it. The survivors increase in numbers, like bacteria tend to do, starting from a population of ten to a thousand bacteria per milliliter in the duodenum, and gradually increasing to up to ten-million per milliliter by the time they reach the depths of the ileum.6 But bacteria aren't strong swimmers—even motile bacteria can't make headway against the downward flow in the small intestine. So, while they increase in numbers as the digestive process proceeds through the small intestine, they can’t go backwards to have a nosh on your next meal. This naturally keeps their numbers down... until they get to the cecum.

Starting in the cecum, the story changes. Things slow down here, and it becomes a freaking free-for-all. Bacteria have plenty of room to spread out, mix, mingle, and really start multiplying. There's even a sheltered spot in the cecum, the appendix, where bacteria can hang out and take a coffee break, without being swept along in the current.

You'd think then, that the fresh bacteria coming into the cecum from the small intestine would be happy to find themselves in this bacterial paradise. Well, no, because there's a catch. The catch is, the cecum is already packed, wall to wall, with a trillion bacteria per milliliter—and these bacteria do not want to share.

The native bacteria defend their territory against any newcomers by secreting anti-microbial factors, out-competing newcomers for access to nutrients, or even physically crowding them out. That’s good news for us, because the native bacteria are generally harmless, whereas the newcomer bacteria might well be intestinal terrorists. The inherent xenophobia of our hoards of redneck gut bacteria helps keep evil foreigner bacteria from getting a foothold.6

Of course, they aren't doing it for our benefit, and they can also keep entirely harmless bacteria from getting a foothold. The redneck bacteria will happily crowd out noble, hardworking immigrant bacteria, even though the immigrants just want to contribute and make a better life for their children.

Anywho.

Since bacterial content jumps so dramatically in the cecum, that's where we stop calling it chyme and start calling it feces.

From the cecum, intermittent contractions push feces uphill into the colon. These contractions, however, are not in it to win it, and a large portion of feces is allowed to fall back down into the sack-like cecum. Hey, we all knew it: shit rolls downhill. This appears to serve a mixing function.7 If this mixing didn't occur, the native bacteria wouldn't be evenly mixed in among the newcomers, and harmful newcomer bacteria might be able to find a warm, shady spot at the bottom of the cecum, where they could increase their numbers and get a foothold. By frequently mingling bacteria from our existing colony with the newcomers, we keep the advantage with the more multitudinous home team.

Which is where we'll close out for this time. Next time, we'll scurry deeper into the colon! You don't want to miss that.

**

If you liked the cecum, you'll love the other parts of the gastrointestinal system!

Digestive System, Part 1: Teeth and Spit

Digestive System, Part 2: Swallowing

Digestive System, Part 3: Down the Tubes

Digestive System, Part 4: B-12 as Temptress

Digestive System, Part 5: The Duodenum

Digestive System, Part 6: The Jejunum

Digestive System, Part 7: The Ileum

Digestive System, Part 8: Liver and Cecum (this article)

Digestive System, Part 9: The Colon

Digestive System, Part 10: The Bitter End

**

Citations and References

1. Alcohol in Health and Disease. 2005 Ed. Pg. 87

2. Racanelli & Rehermann. The Liver as an Immunological Organ. Hepatology 43, S1.

3. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism. 6th ed. Pg. 255.

4. Lajtha & Vane. Dependence of Bone Marrow Cells on the Liver for Purine Supply. Nature 182, 191-192.

5. The Physiologic Basis of Surgery, 4th Ed. Pg. 501.

6. O’Hara and Shanahan. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Reports. 2006 July;7(7):688-693

7. Schuster Atlas of Gastrointestinal Motility: In Health and Disease. Pg. 247.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.